19 Dec 2016

This semester has gone a little too fast for my liking. Though there were plenty of good memories and takeaways from this semester, it has been by far my most stressful time in this college yet. Between taking on a number of technical projects and trying to rescue a sharply falling SG due to a poor T1, there has been very little free time this sem. Above all, this sem has shown me just how limited of a resource brain power is. Thinking about solving problems wears me out much more easily than it used to.

That's not to say what I've been doing is all drudgery. Some interesting projects that I've been working on:

GSoC 2016 Project - kio-stash

Yup, this project has been in the pipeline for months. While it (mostly) works on a clean install of KDE, it has some bugs with copying with mtp:/ device slaves and isn't very well integrated with Dolphin yet. It is in my best interest to have this shipped with KDE Frameworks as soon as possible, so I'm looking into patching Dolphin with better, more specific action support for my project.

IEEE Signal Processing Cup 2017 - Real-Time Beat Tracking Challenge

The premise of this project doesn't seem very complicated - a team just needs to submit an algorithm which can successfully detect the beats in a song in real-time on an embedded device. Heck, I had already implemented the same on an Arduino with a microphone for rather fancy lighting in my hostel room. Unfortunately, as I've learned the hard way, anything that looks simple is deceptive and this project is a perfect example. For one thing, a song by itself in the amplitude-time domain is nearly impossible to extract any data from, so it requires a (Fast) Fourier Transform to extract frequency bin amplitudes to get anything useful from it. Next, obtaining beat onset and detection requires generating a tempogram to find the BPM of a song to find the approximate beat positions. There are many interesting approaches and different algorithms to solve this problem. Fortunately, I'm not doing this alone and the seniors I'm working with have a better understanding of the more difficult mathematical components of this project, leaving me free to code in C++ and deploy it on actual hardware.

foss@bphc

This project is a society on campus I started with threeprogrammers far more competent than myself. It all started in September this year when we had the two-day long Wikimedia Hackathon on campus. Though my contribution to Wikimedia was small, I got a lot out of the hackathon by meeting the people from Amrita University who came for organising the event. Listening to what Tony and Srijan had to say about how much working for foss@amrita had benefited them made me realise how much room for improvement there was in BPHC. As far as this society goes, things are still in their infancy, yet I feel there is just enough critical mass of talent and enthusiasm in open source development to push this society forward. We even have our own Constitution!

Making a personal website?

While Blogspot has been a faithful home for this blog for over half a decade, it is time to move to a modern solution for hosting. Plus setting up a website will teach me a bit about web development too, and I've needed an excuse to learn it for a while. Surely it can't be all that hard, right?

Burnout

While the slew of all these technical projects seemed like a good idea at the time, it has pushed me closer to burning out. It is the same feeling as what I felt the same time last year, albeit for different reasons.

Some of it has carried over from studying harder at the end of this sem than I had done so before. To my surprise, studying under pressure was actually more effective than it was without. In some ways, it was a throwback to studying for the number of exams nearly a couple of years ago. It has made me question whether any of my education was as much for the knowledge as it was for the desperation of avoiding failure. I still haven't figured it out, but at least I feel like I'm not as adverse to putting in the hours for getting a decent CGPA as I had been last semester.

There have been compromises in other spheres of college life as well, investing so much time in studying or doing projects has made me cut down my participation in other clubs and I've quit nearly all the non-technical clubs I joined last year. There's more than that too - I feel it's much harder to be fully immersed in anything anymore.

Maybe it's just something else which requires more soul searching.

29 Aug 2016

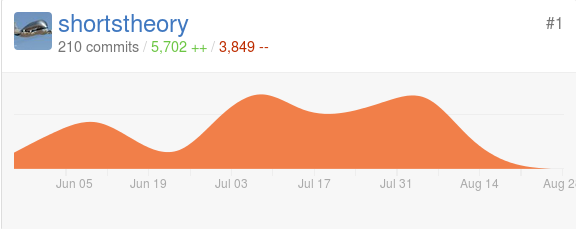

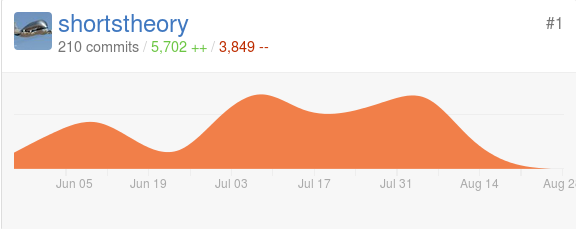

That’s it. After a combined total of 217 git commits, 6,202 lines of code added, and 4,167 lines of code deleted, GSoC 2016 is finally over.

These twelve weeks of programming have been a very enriching experience for me and making this project has taught me a lot about production quality software development. Little did I know that a small project I had put together in a 6 hour session of messing around with Qt would lead to something as big as this!

There have been many memorable moments throughout my coding period for the GSoC - such as the first time I got an ioslave to install correctly, to writing its “Hello World” equivalent, and getting a basic implementation of the project up and running by doing a series of dirty hacks with Dolphin’s code. There were also times when I was so frustrated with debugging for this project, that I wanted to do nothing but smash my laptop’s progressively failing display panel with the largest hammer I could find. The great mentorship from my GSoC mentor and the premise of the GSoC program itself kept me going. This also taught me an important lesson with regards to software development - no one starting out gets it right on their first try. It feels like after a long run of not quite getting the results I wanted, the GSoC is the thing which worked out for me as everything just fell into place.

There’s a technical digression here, which you can feel free to skip through if you don’t want to get into the details of the project.

Following up from the previous blog post, with the core features of the application complete, I had moved on to unit testing my project. For this project, unit testing involved writing test cases for each and every component of the application to find and fix any bugs. Despite the innocuous name, unit testing this project was a much bigger challenge than I expected. As for one thing, the ioslave in my project is merely a controller in the MVC system of the virtual Stash File System, the Dolphin file manager, and the KIO Slave itself. Besides, most of the ioslave’s functions have a void return type, so feeding the slave’s functions’ arguments to get an output for checking was not an option either.

This led me to use an approach, which my mentor aptly called “black box testing”.

In this approach, one writes unit tests testing for a specific action and then checking for whether the effects of the said action are as expected. In this case, the ioslave was tested by giving it a test file and then apply some of the ioslave’s functions such as copy, rename, delete, and stat. From there, through a bunch of QVERIFY calls is to check whether the ioslave has completed the operation successfully. Needless to say, this approach is far more convoluted to write unit tests for as it required checking each and every test file for its properties in every test case. Fortunately, the QTestLib API is pretty well documented so it wasn’t difficult to get started with writing unit tests. I also had a template of what a good test suite should look like thanks to David Faure’s excellent work on implementing automated unit testing for the Trash ioslave. With these two tools in hand, I started off with writing unit tests shortly before the second year of college started.

As expected, writing black box unit tests was a PITA in its own right. The first time I ran my unit test I came up with a dismal score of 6 unit tests passed out of the 17 I had written. This lead me to go back and check whether my unit tests were testing correctly at all. It turned out that I had made so many mistakes with writing the unit tests that an entire rewrite of the test suite wasn’t unwarranted.

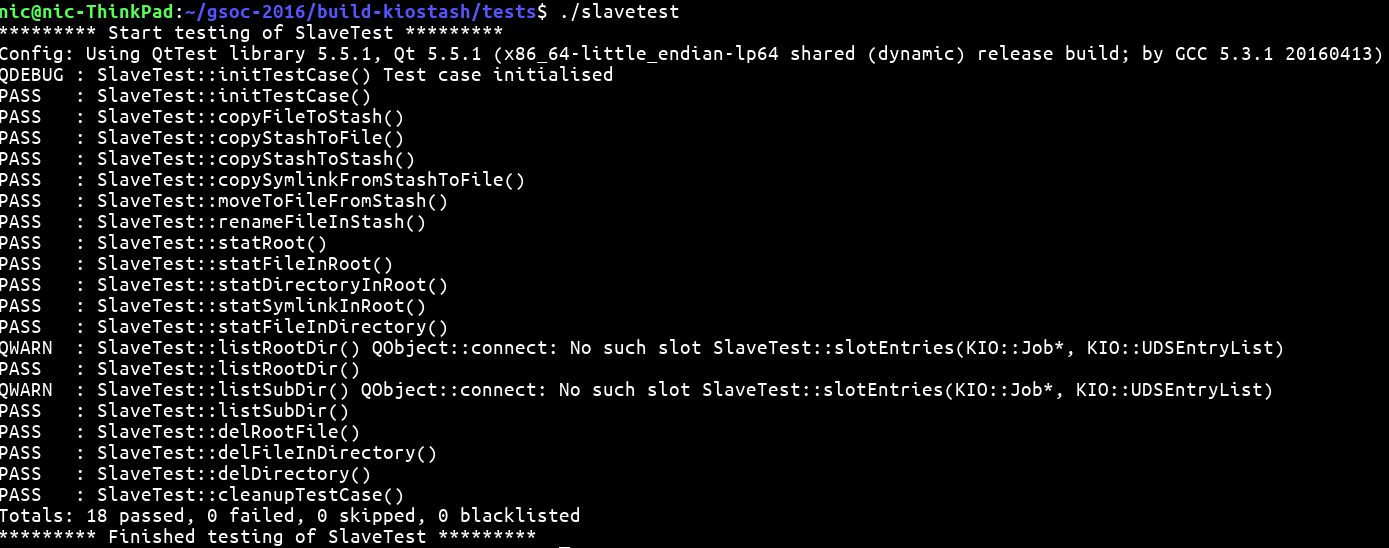

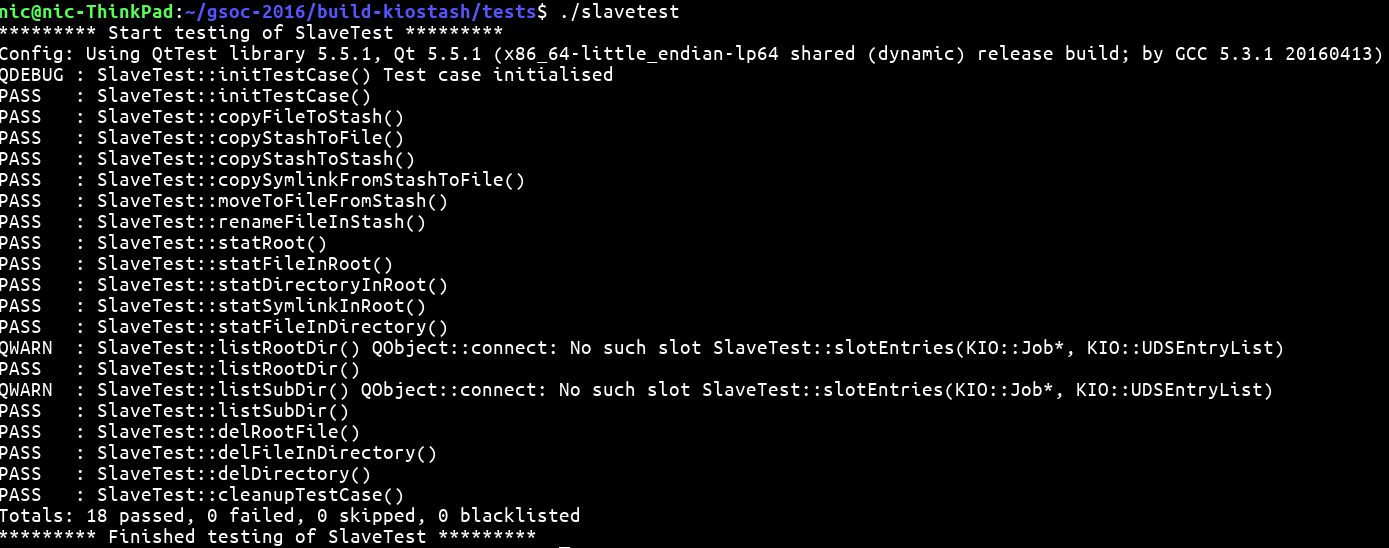

With a rewrite of the test cases completed, I ran the test suite again. The results were a bit better - 13 out of the 17 test cases passed, but 4 failed test cases - enough reason for the project to be unshippable. Looking into the issue a bit deeper, I found out that all the D-Bus calls to my ioslave for copy and move operations were not working correctly! Given that I had spent so much time on making sure the ioslave was robust enough, this was a mixed surprise. Finally, after a week of rewriting and to an extent, refactoring the rename and copy functions of the ioslave, I got the best terminal output I ever wanted from this project.

Definitely the highest point of the GSoC for me. From there on out, it was a matter of putting the code on the slow burner for cleaning up any leftover debug statements and for writing documentation for other obscure sections. With a net total of nearly 2000 lines of code, it far surpasses any other project I’ve done in terms of size and quality of code written.

At some points in the project, I felt that the stipend was far too generous, for many people working on KDE voluntarily produce projects much larger thann mine. In the end, I feel the best way to repay the generosity is to continue with open source development - just as the GSoC intended. Prior to the GSoC, open source was simply an interesting concept to me, but contributing a couple of thousands of lines of code to an open source codebase has made me realise just how powerful open source is. There were no restrictions on when I had to work (usually my productivity was at its peak at outlandish late night hours), on the machine I used for coding (a trusty IdeaPad, replaced with a much nicer ThinkPad), or on the place where I felt most comfortable coding from (a toss up between my much used study table or the living room). In many ways, working from home was probably the best environment I could ask for when it came to working on this project. Hacking on an open source project gave me a sense of gratification solving a problem in competitive programming never could have.

The Google Summer of Code may be over, but my journey with open source development has just begun. Here’s to even bigger and better projects in the future!

21 Jul 2016

I'm a lot closer to finishing the project now. Thanks to some great support from my GSoC mentor, my project has turned out better than what I had written about in my proposal! Working together, we've made a lot of changes to the project.

For starters, we've changed the name of the ioslave from "File Tray" to "staging" to "stash". I wasn't a big fan of the name change, but I see the utility in shaving off a couple of characters in the name of what I hope will be a widely used feature.

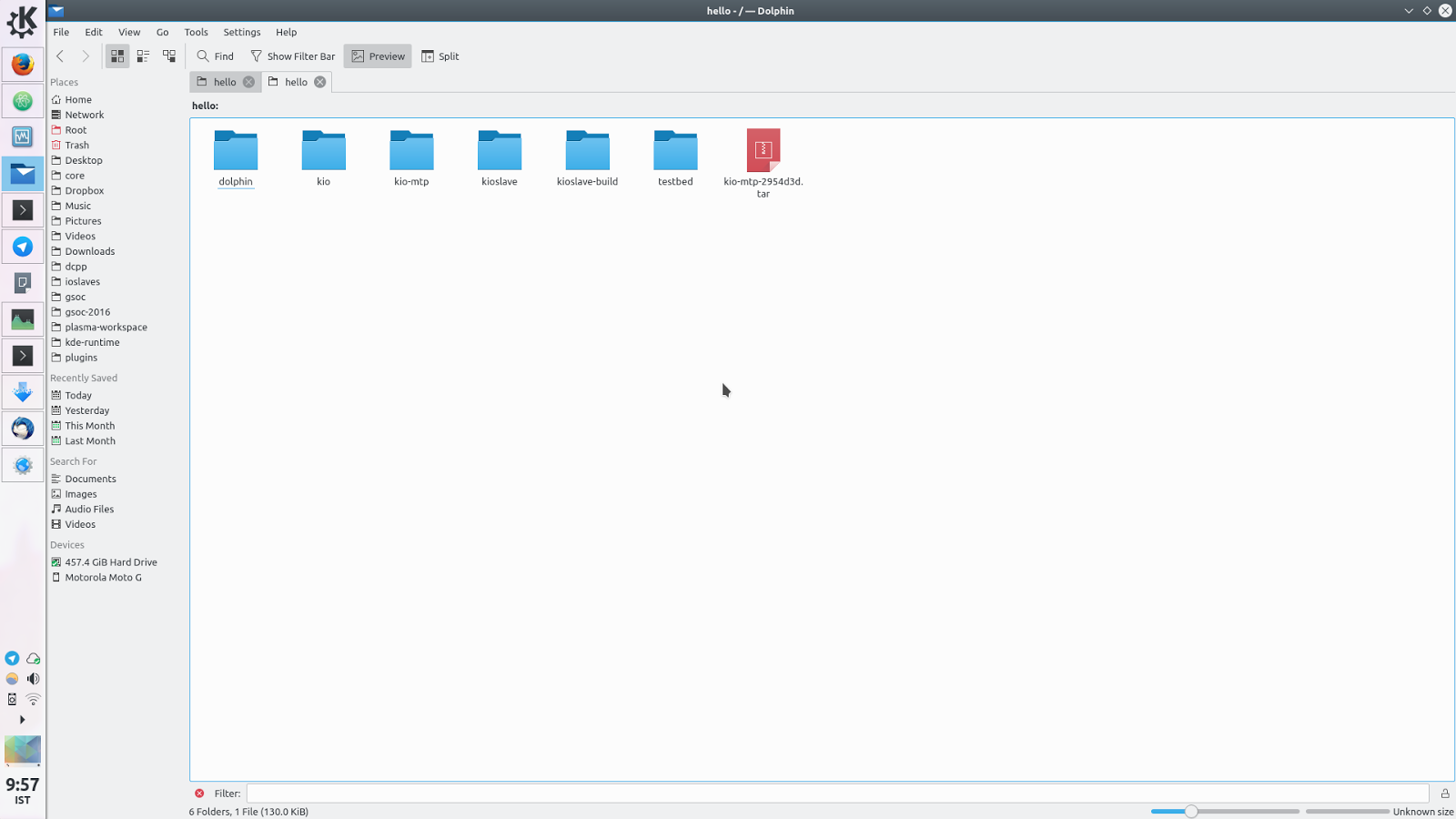

Secondly, the ioslave is now completely independent from Dolphin, or any KIO application for that matter. This means it works exactly the same way across the entire suite of KIO apps. Given that at one point we were planning to make the ioslave fully functional only with Dolphin, this is a major plus point for the project.

Next, the backend for storing stashed files and folders has undergone a complete overhaul. The first iteration of the project stored files and folders by saving the URLs of stashed items in a QList in a custom "stash" daemon running on top of kded5. Although this was a neat little solution which worked well for most intents and purposes, it had some disadvantages. For one, you couldn't delete and move files around on the ioslave without affecting the source because they were all linked to their original directories. Moreover, with the way 'mkdir' works in KIO, this solution would never work without each application being specially configured to use the ioslave which would entail a lot of groundwork laying out QDBus calls to the stash daemon. With these problems looming large, somewhere around the midterm evaluation week, I got a message from my mentor about ramping up the project using a "StashFileSystem", a virtual file system in Qt that he had written just for this project.

The virtual file system is a clever way to approach this - as it solved both of the problems with the previous approach right off the bat - mkdir could be mapped to virtual directory and now making volatile edits to folders is possible without touching the source directory. It did have its drawbacks too - as it needed to stage every file in the source directory, it would require a lot more memory than the previous approach. Plus, it would still be at the whims of kded5 if a contained process went bad and crashed the daemon.

Nevertheless, the benefits in this case far outweighed the potential cons and I got to implementing it in my ioslave and stash daemon. Using this virtual file system also meant remapping all the SlaveBase functions to corresponding calls to the stash daemon which was a complete rewrite of my code. For instance, my GitHub log for the week of implementing the virtual file system showed a sombre 449++/419–. This isn't to say it wasn't productive though - to my surprise the virtual file system actually worked better than I hoped it would! Memory utilisation is low at a nominal ~300 bytes per stashed file and the performance in my manual testing has been looking pretty good.

With the ioslave and other modules of the application largely completed, the current phase of the project involves integrating the feature neatly with Dolphin and for writing a couple of unit tests along the way. I'm looking forward to a good finish with this project.

You can find the source for it here: https://github.com/KDE/kio-stash (did I mention it's now hosted on a KDE repo? ;) )

21 Jun 2016

This project has been going well. Though it was expectedly difficult in the beginning, I feel like I am on the other side of the learning curve now. I will probably make a proper update post sometime later this month. My repo for this project can be found here: https://github.com/shortstheory/kio-stash

For now, this is a small tutorial for writing KDE I/O slaves (KIO slaves) which can be used for a variety of KDE applications. KIO slaves are a great way for accessing files from different filesystems and protocols in a neat, uniform way across many KDE applications. Their versatility makes them integral to the KIO library. KIO slaves have changed in their structure the transition to KF5 and this tutorial highlights some of these differences from preceding iterations of it.

Project Structure

For the purpose of this tutorial, your project source directory needs to have the following files.

- kio_hello.h

- kio_hello.cpp

- hello.json

- CMakeLists.txt

If you don't feel like creating these yourself, just clone it from here: https://github.com/shortstheory/kioslave-tutorial

hello.json

The .json file replaces the .protocol files used in KIO slaves pre KF5. The .json file for the KIO slave specifies the properties the KIO slave will have such as the executable path to the KIO slave on installation. The .json file also includes properties of the slave such as being able to read from, write to, delete from, among many others. Fields in this .json file are specified from the KProtocolManager class. For creating a KIO slave capable of showing a directory in a file manager such as Dolphin, the listing property must be set to true. As an example, the .json file for the Hello KIO slave described in this tutorial looks like this:

{

"KDE-KIO-Protocols" : {

"hello": {

"Class": ":local",

"X-DocPath": "kioslave5/kio_hello.html",

"exec": "kf5/kio/hello",

"input": "none",

"output": "filesystem",

"protocol": "hello",

"reading": true

}

}

}

As for the CMakeLists.txt, you will need to link your KIO slave module with KF5::KIOCore. This can be seen in the project directory.

kio_hello.h

#ifndef HELLO_H

#define HELLO_H

#include <kio/slavebase.h>

/**

This class implements a Hello World kioslave

*/

class Hello : public QObject, public KIO::SlaveBase

{

Q_OBJECT

public:

Hello(const QByteArray &pool, const QByteArray &app);

void get(const QUrl &url) Q_DECL_OVERRIDE;

};

#endif

The Hello KIO slave is derived from KIO::SlaveBase. The SlaveBase class has some basic functions already implemented for the KIO slave. This can be found in the documentation. However, most of the functions of SlaveBase are virtual functions and have to be re-implemented for the KIO slave. In this case, we are re-implementing the get function to print a QString when it is called by kioclient5.

In case you don't need special handling of the KIO slave's functions, you can derive your KIO slave class directly from KIO::ForwardingSlaveBase. Here, you would only need to re-implement the rewriteUrl function to get your KIO slave working.

kio_hello.cpp

#include "hello.h"

#include <QDebug>

class KIOPluginForMetaData : public QObject

{

Q_OBJECT

Q_PLUGIN_METADATA(IID "org.kde.kio.slave.hello" FILE "hello.json")

};

extern "C"

{

int Q_DECL_EXPORT kdemain(int argc, char **argv)

{

qDebug() << "Launching KIO slave.";

if (argc != 4) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: kio_hello protocol domain-socket1 domain-socket2\n");

exit(-1);

}

Hello slave(argv[2], argv[3]);

slave.dispatchLoop();

return 0;

}

}

void Hello::get(const QUrl &url)

{

qDebug() << "Entering function.";

mimeType("text/plain");

QByteArray str("Hello world!\n");

data(str);

finished();

qDebug() << "Leaving function";

}

Hello::Hello(const QByteArray &pool, const QByteArray &app)

: SlaveBase("hello", pool, app) {}

#include "hello.moc"

The .moc file is, of course, auto-generated at compilation time.

As mentioned earlier, the KIO Slave's .cpp file will also require a new KIOPluginForMetaData class to add the .json file. The following is used for the hello KIO slave and can be used as an example:

class KIOPluginForMetaData : public QObject

{

Q_OBJECT

Q_PLUGIN_METADATA(IID "org.kde.kio.slave.hello" FILE "hello.json")

};

CMakeLists.txt

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.5)

set(QT_MIN_VERSION "5.4.0")

set(KF5_MIN_VERSION "5.16.0")

find_package(ECM ${KF5_MIN_VERSION} REQUIRED NO_MODULE)

set(

CMAKE_MODULE_PATH

${CMAKE_MODULE_PATH}

${ECM_MODULE_PATH}

${ECM_KDE_MODULE_DIR}

)

include(KDEInstallDirs)

include(KDECMakeSettings)

include(KDECompilerSettings NO_POLICY_SCOPE)

include(ECMSetupVersion)

include(FeatureSummary)

add_library(kio_hello MODULE hello.cpp)

find_package(KF5 ${KF5_MIN_VERSION} REQUIRED KIO)

target_link_libraries(kio_hello KF5::KIOCore)

set_target_properties(kio_hello PROPERTIES OUTPUT_NAME "hello")

install(TARGETS kio_hello DESTINATION ${KDE_INSTALL_PLUGINDIR}/kf5/kio )

Installation

Simply run the following commands in the source folder:

mkdir build

cd build

cmake -DCMAKE_INSTALL_PREFIX=/usr -DKDE_INSTALL_USE_QT_SYS_PATHS=TRUE ..

make

sudo make install

kdeinit5

As shown above, we have to run kdeinit5 again so the new KIO slave is discovered by KLauncher and can be loaded when we run a command through an application such as kioclient5.

Run:

kioclient5 \'cat\' \'hello:/\'

And the output should be:

30 May 2016

I have officially started my GSoC project under the mentorship of Boudhayan Gupta and Pinak Ahuja.

The project idea's implementation has undergone some changes from what I proposed. While the essence of the project is the same, it will now no longer be dependent on Baloo and xattr. Instead, it will use a QList to hold a list of staged files with a plugin to kiod. My next milestone before the mid-term evaluation is to implement this in a KIO slave which will be compatible with the whole suite of KDE applications.

For the last two weeks, I've been busy with going through hundreds of lines of source code to understand the concept of a KIO slave. The KIO API is a very neat feature of KDE - it provides a single, consistent way to access remote and local filesystems. This is further expanded to KIO slaves which are programs based on the KIO API which allow for a filesystem to be expressed in a particular way. For instance, there is a KIO slave for displaying xattr file tags as a directory under which each file marked to a tag would be displayed. KIO slaves even expand to network protocols allowing for remote access using slaves such as http:/, ftp:/, smb:/ (for Windows samba shares), fish:/, sftp:/, nfs:/, and webdav:/. My project requires virtual folder constructed of URLs stored in a QList - an ideal fit for KIO slaves.

However, hacking on KIO slaves was not exactly straightforward. Prior to my GSoC selection, I had no idea on how to edit CMakeLists.txt files and it was a task to learn to make one by hand. Initially, it felt like installing the dependencies for building KIO slaves would almost certainly lead to me destroying my KDE installation, and sure enough, I did manage to ruin my installation. Most annoying. Fortunately, I managed to recover my data and with a fresh install of Kubuntu 16.04 with all the required KDE packages, I got back to working on getting the technical equivalent of a Hello World to work with a KIO slave.

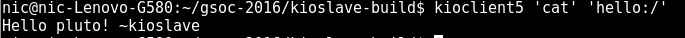

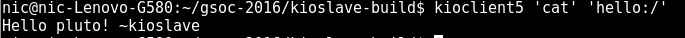

This too, was more than a matter of just copying and pasting lines of code from the KDE tutorial. KIO slaves had dropped the use of .protocol files in the KF5 transition, instead opting for JSON files to store the properties of the KIO slave. Thankfully, I had the assistance of the legendary David Faure. Under his guidance, I managed to port the KIO slave in the tutorial to a KF5 compatible KIO slave and after a full week of frustration of dealing with dependency hell, I saw the best Hello World I could ever hope for:

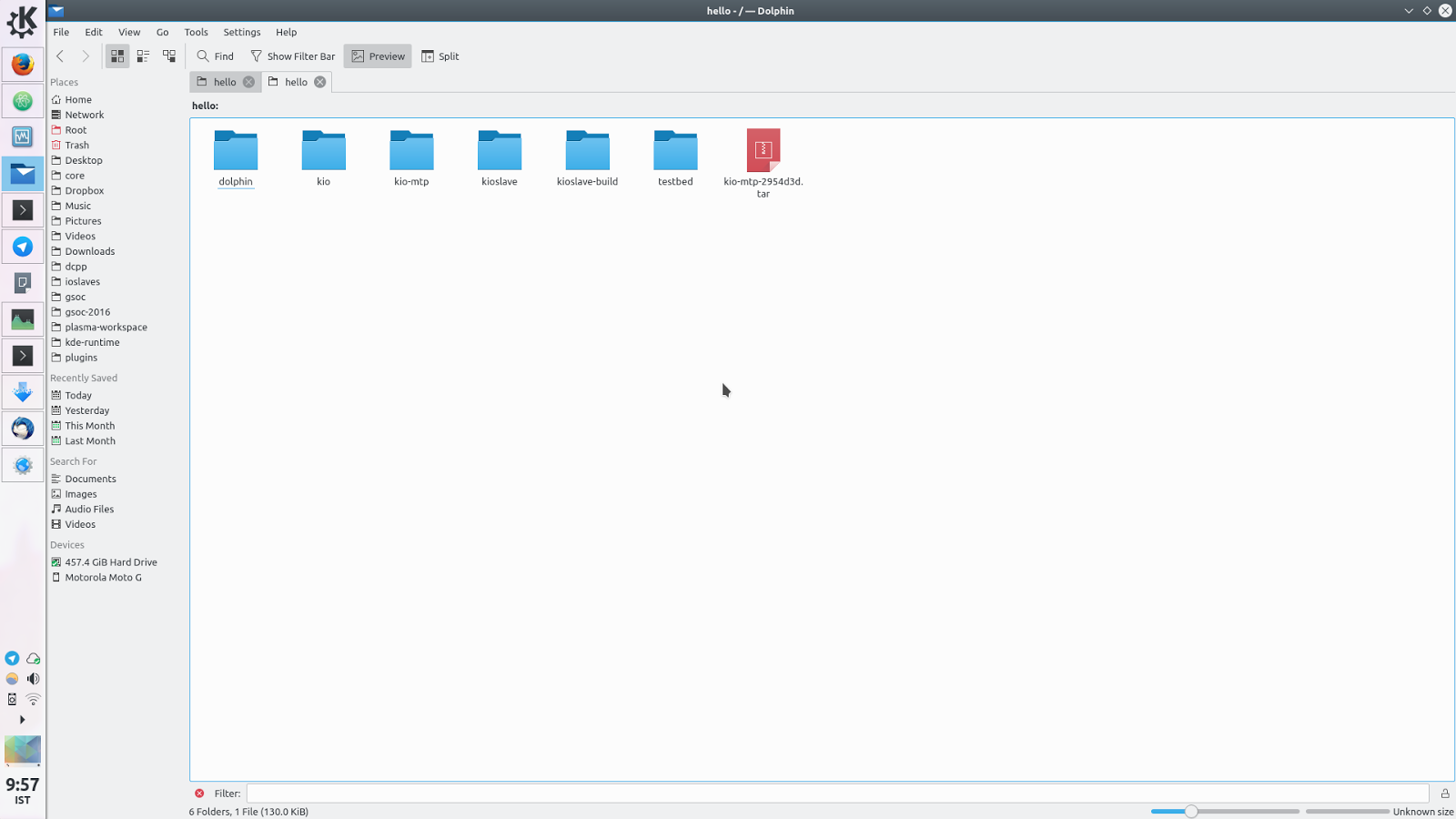

Baby steps. The next step was to make the KIO slave capable of displaying the contents of a specified QUrl in a file manager. The documentation for KProtocolManager made it seem like a pretty straightforward task - apparently that all I needed to do was to add a "listing" entry in my JSON protocol file and I would have to re-implement the listDir method inherited from SlaveBase using a call to SlaveBase::listDir(&QUrl). Unbeknownst to me, the SlaveBase class actually didn't have any code for displaying a directory! The SlaveBase class was only for reimplementing its member functions in a derived class as I found out by going through the source code of the core of kio/core. Learning from my mistake here I switched to using a ForwardingSlaveBase class for my KIO slave which instantly solved my problems of displaying a directory.

Fistpump

According to my timeline, the next steps in the project are

- Finishing off the KIO slave by the end of this month

- Making GUI modifications in Dolphin to accommodate the staging area

- Thinking of a better name for this feature?

So far, it's been a great experience to get so much support from the KDE community. Here's to another two and a half months of KDE development!