GSoC 2018 - New Beginnings

05 Jun 2018I'm really excited to say that I'll be working with Ardupilot for the better part of the next two months! Although this is the second time I'm making a foray into Open Source Development, the project at hand this time is quite different from what I had worked on in my first GSoC project.

Ardupilot is an open-source autopilot software for several types of semi-autonomous robotic vehicles including multicopters, fixed-wing aircraft, and even marine vehicles such as boats and submarines. As the name suggests, Ardupilot was formerly based on the Arduino platform with the APM2.x flight controllers which boasted an ATMega2560 processor. Since then, Ardupilot has moved on to officially supporting much more advanced boards with significantly better processors and more robust hardware stacks. That said, these flight controllers contain application specific embedded hardware which is unsuitable for performing intensive tasks such as real-time object detection or video processing.

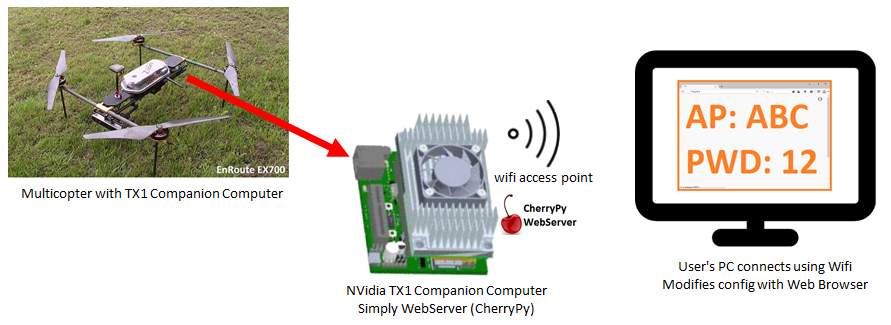

CC Setup with a Flight Computer

APSync is a recent Ardupilot project which aims to ameliorate the limited processing capability of the flight controllers by augmenting them with so-called companion computers (CCs). As of writing, APSync officially supports the Raspberry Pi 3B(+) and the NVidia Jetson line of embedded systems. One of the more popular use cases for APSync is to enable out-of-the-box live video streaming from a vehicle to a laptop. This works by using the CC's onboard WiFi chip as a WiFi hotspot to stream the video using GStreamer. However, the current implementation has some shortcomings which are:

- Only one video output can be unicasted from the vehicle

- The livestreamed video progressively deteriorates as the WiFi link between the laptop and the CC becomes weaker

This is where my GSoC project comes in. My project is to tackle the above issues to provide a good streaming experience from an Ardupilot vehicle. The former problem entails rewriting the video streaming code to allow for sending multiple video streams at the same time. The latter is quite a bit more interesting and it deals with several computer networks and hardware related engineering issues to solve. "Solve" is a subjective term here as there isn't any way to significantly boost the WiFi range from the CC's WiFi hotspot without some messy hardware modifications.

What can be done is to degrade the video quality as gracefully as possible. It's much better to have a smooth video stream of low quality than to have a high quality video stream laden with jitter and latency. At the same time, targeting to only stream low quality video when the WiFi link and the processor of the CC allows for better quality is inefficient. To "solve" this, we would need some kind of dynamically adaptive streaming mechanism which can change the quality of the video streamed according to the strength of the WiFi connection.

My first thought was to use something along the lines of Youtube's DASH (Dynamically Adaptive Streaming over HTTP) protocol which automatically scales the video quality according to the available bandwidth. However, DASH works in a fundamentally different way from what is required for adaptive livestreaming. DASH relies on having the same video pre-encoded in several different resolutions and bitrates. The server estimates the bandwidth of its connection to the client. On doing so, the server chooses one of the pre-encoded video chunks to send to the client. Typically, the server tries to guess which video chunk can deliver the best possible quality without buffering.

Youtube's powerful servers have no trouble encoding a video several times, but this approach is far too intensive to be carried out on a rather anemic Raspberry Pi. Furthermore, DASH relies on QoS (short for Quality of Service which includes parameters like bitrate, jitter, packet loss, etc) reports using TCP ACK messages. This causes more issues as we need to stream the video down using RTP over UDP instead of TCP. The main draw of UDP for livestreaming is that performs better than TCP does on low bandwidth connections due to its smaller overhead. Unlike TCP which places guarantees on message delivery through ACKs, UDP is purely best effort and has no concept of ACKs at the transport layer. This means we would need some kind of ACK mechanism at the application layer to measure the QoS.

Enter RTCP. This is the official sibling protocol to RTP which among other things, reports packet loss, cumulative sequence number received, and jitter. In other words - it's everything but the kitchen sink for QoS reports for multimedia over UDP! What's more, GStreamer natively integrates RTCP report handling. This is the approach I'll be using for getting estimated bandwidth reports from each receiver.

I'll be sharing my experiences with the H.264 video encoders and hardware in my next post.